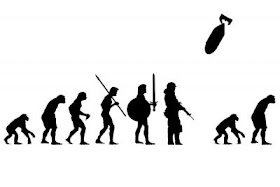

La especie viva más cercana a la nuestra es la de los chimpancés. Jane Goodall los estudia en África desde hace 40 años. Lo que comenzó como una aventura individual se volvió, con el tiempo, un trabajo de equipo, y, en la actualidad, es una organización que realiza una importante actividad que va mucho más allá de la observación de campo de nuestros primos. Salvar a los chimpancés es uno de sus objetivos, y entra dentro de otro de mayor calado, el de salvar la naturaleza, y el de salvarnos, con ella, a nosotros mismos. Una vez más, el altruismo revela, en sus profundidades, un egoísmo inteligente. La moral de amplio calado, que abarque más allá de nosotros y de nuestros más cercanos allegados, requiere un aparato cognitivo que realice abstracciones, cree categorías y juegue adecuadamente con ellas, así como de un sistema emocional mamífero basado en las vinculación madre-hijo. También es preciso un entorno de relativa prosperidad, en el que exista una ligera liberación de la necesidad, al menos de la inmediatez de la necesidad. Somos más generosos con la tripa llena y la supervivencia relativamente garantizada. La ley de la selva se supera con la civilización.....en parte. Aunque no están genéticamente determinadas nuestras conductas de forma absoluta, sí somos un diseño biológico, un producto de la evolución y, como tales, tenemos algunos programas invariables. Las tendencias violentas masculinas parecen ser uno de ellos, y afloran casi siempre bajo determinadas circunstancias.

La especie viva más cercana a la nuestra es la de los chimpancés. Jane Goodall los estudia en África desde hace 40 años. Lo que comenzó como una aventura individual se volvió, con el tiempo, un trabajo de equipo, y, en la actualidad, es una organización que realiza una importante actividad que va mucho más allá de la observación de campo de nuestros primos. Salvar a los chimpancés es uno de sus objetivos, y entra dentro de otro de mayor calado, el de salvar la naturaleza, y el de salvarnos, con ella, a nosotros mismos. Una vez más, el altruismo revela, en sus profundidades, un egoísmo inteligente. La moral de amplio calado, que abarque más allá de nosotros y de nuestros más cercanos allegados, requiere un aparato cognitivo que realice abstracciones, cree categorías y juegue adecuadamente con ellas, así como de un sistema emocional mamífero basado en las vinculación madre-hijo. También es preciso un entorno de relativa prosperidad, en el que exista una ligera liberación de la necesidad, al menos de la inmediatez de la necesidad. Somos más generosos con la tripa llena y la supervivencia relativamente garantizada. La ley de la selva se supera con la civilización.....en parte. Aunque no están genéticamente determinadas nuestras conductas de forma absoluta, sí somos un diseño biológico, un producto de la evolución y, como tales, tenemos algunos programas invariables. Las tendencias violentas masculinas parecen ser uno de ellos, y afloran casi siempre bajo determinadas circunstancias. Michael Patrick Ghiglieri comenzó trabajando con Goodall en la Reserva de Gombe, en Tanzania, pero por razones políticas (intento de secuestro de Goodall incluido) acabó en el bosque de Kibale, en Ruanda. Allí realizó un estudio meticuloso de la ecología chimpancé. La primera medida que adoptó fue la de no darles comida, cosa que se estilaba en Gombe. Creía Ghiglieri que esto perturbaría el comportamiento del grupo primate de forma tal que no pudiese apreciarse cómo eran verdaderamente los chimpancés en estado salvaje. Ghiglieri tomó medidas del territorio, de los consumos alimentarios, de los tamaños de grupo, de los árboles frutales, etc etc. Concluyó que la estructura grupal de los chimpancés en estado salvaje es de fusión-fisión. Los chimpancés forman grupos pequeños y en ocasiones van solos en busca del alimento, y cuando hay suficiente se reúnen en grupos mayores. Son animales extremadamente sociales, que necesitan esos momentos de reunión. Otra de las características de los grupos chimpancés, es la exogamia femenina. Son las hembras las que, a diferencia de lo que sucede en otras muchas especies primates, abandonan el grupo al llegar a su madurez sexual. Esto crea grupos con un núcleo duro de machos genéticamente emparentados rodeado de una constelación de hembras venidas de otros grupos. Los machos forman, de esta manera, una unidad de interés genético. Dado que comparten sus genes también comparten a sus hembras, y también otros recursos vitales. El enemigo está siempre fuera del grupo: el enemigo es el otro. Ghiglieri cree que los humanos somos, al igual que los chimpancés, animales con una mente diseñada para operar dentro de grupos excluyentes, que se hacen la guerra. Tenemos en común con ellos un 99% del genoma y un origen africano.

Michael Patrick Ghiglieri comenzó trabajando con Goodall en la Reserva de Gombe, en Tanzania, pero por razones políticas (intento de secuestro de Goodall incluido) acabó en el bosque de Kibale, en Ruanda. Allí realizó un estudio meticuloso de la ecología chimpancé. La primera medida que adoptó fue la de no darles comida, cosa que se estilaba en Gombe. Creía Ghiglieri que esto perturbaría el comportamiento del grupo primate de forma tal que no pudiese apreciarse cómo eran verdaderamente los chimpancés en estado salvaje. Ghiglieri tomó medidas del territorio, de los consumos alimentarios, de los tamaños de grupo, de los árboles frutales, etc etc. Concluyó que la estructura grupal de los chimpancés en estado salvaje es de fusión-fisión. Los chimpancés forman grupos pequeños y en ocasiones van solos en busca del alimento, y cuando hay suficiente se reúnen en grupos mayores. Son animales extremadamente sociales, que necesitan esos momentos de reunión. Otra de las características de los grupos chimpancés, es la exogamia femenina. Son las hembras las que, a diferencia de lo que sucede en otras muchas especies primates, abandonan el grupo al llegar a su madurez sexual. Esto crea grupos con un núcleo duro de machos genéticamente emparentados rodeado de una constelación de hembras venidas de otros grupos. Los machos forman, de esta manera, una unidad de interés genético. Dado que comparten sus genes también comparten a sus hembras, y también otros recursos vitales. El enemigo está siempre fuera del grupo: el enemigo es el otro. Ghiglieri cree que los humanos somos, al igual que los chimpancés, animales con una mente diseñada para operar dentro de grupos excluyentes, que se hacen la guerra. Tenemos en común con ellos un 99% del genoma y un origen africano. Gracias al notable desarrollo tecnológico y económico de nuestra civilización (debido, todo sea dicho, al comercio, al intercambio que superan barreras nacionales, étnicas y raciales –tomen nota los liberticidas) podemos expresar lo mejor de nuestros instintos, nuestra también natural benevolencia. Pero la lucha por el poder y por los recursos, la lucha por acceder a las hembras y por imponerse al extraño, siguen enturbiando las relaciones sociales, tanto en los foros internacionales como dentro de cada nación, cada ciudad y cada vecindario. El lado oscuro del hombre se manifiesta a través de violaciones, asesinatos y, en mayor escala, a través de guerras y genocidios. El macho que encuentre dificultades severas para aparearse con hembras de su gusto podrá tomarlas por la fuerza, cuando crea que puede hacerlo sin peligro. Igualmente, si puede obtener los recursos con los que conquistar a una hembra de forma fraudulenta o violenta, a falta de capacidad u oportunidad de hacerlo de forma honrada y pacífica, lo hará. Ya hemos hablado aquí del lado amable del hombre. Quien quiera mirar a la otra cara de Jano, la siniestra, y comprender de esta forma cabalmente lo que somos, deberá leer el libro de Ghiglieri sobre el particular.

Gracias al notable desarrollo tecnológico y económico de nuestra civilización (debido, todo sea dicho, al comercio, al intercambio que superan barreras nacionales, étnicas y raciales –tomen nota los liberticidas) podemos expresar lo mejor de nuestros instintos, nuestra también natural benevolencia. Pero la lucha por el poder y por los recursos, la lucha por acceder a las hembras y por imponerse al extraño, siguen enturbiando las relaciones sociales, tanto en los foros internacionales como dentro de cada nación, cada ciudad y cada vecindario. El lado oscuro del hombre se manifiesta a través de violaciones, asesinatos y, en mayor escala, a través de guerras y genocidios. El macho que encuentre dificultades severas para aparearse con hembras de su gusto podrá tomarlas por la fuerza, cuando crea que puede hacerlo sin peligro. Igualmente, si puede obtener los recursos con los que conquistar a una hembra de forma fraudulenta o violenta, a falta de capacidad u oportunidad de hacerlo de forma honrada y pacífica, lo hará. Ya hemos hablado aquí del lado amable del hombre. Quien quiera mirar a la otra cara de Jano, la siniestra, y comprender de esta forma cabalmente lo que somos, deberá leer el libro de Ghiglieri sobre el particular.Michael ha tenido la amabilidad de respondernos unas preguntas. Gracias a Marzo, una vez más, por traducirlas.

En ingles:

1.-What is the difference between violence exercised by individuals and by groups? Can we speak of a micro and a macroviolence?

1.-What is the difference between violence exercised by individuals and by groups? Can we speak of a micro and a macroviolence?

As far as I see it, the differences between violence exercised between individuals versus that between groups mainly revolve around the perceived or imagined idea that the risk(s) to the perpetrators seems to be less for individuals in the group than the risk to be incurred by one man were he to go out in single combat against a single enemy opponent. In a group, each man may each imagine that someone else among them will be the one who suffers, not him. The other major difference is various sorts of propaganda or polemics or political discussion emerges as emotional grease to validate in advance an offensive by a social group, whereas nearly nothing of this sort occurs before one individual commits offensive violence.

I think distinctions made in the spectrum of violence as "macro" and "micro-" violence are silly. How many times does one need to be beat up or murdered to begin thinking of any violence as "micro?" In short, violence is employed mainly to steal what the victim has, whether that victim is a single young woman or a neighboring nation. Once a certain level of violence has attained its goal--the surrendering of what the aggressor(s) want to steal--the need for violence has passed. Sometimes mere coercion (as is the ultimate goal of terrorism) by threat is all that is needed. But when no violence at all occurs except words of threat, can we call it "micro?" I think not. All violence is "macro."

2.-Regarding the violence exercised by groups, could we distinguish that exerted towards exogroups from that which is exercised within endogroups?

2.-Regarding the violence exercised by groups, could we distinguish that exerted towards exogroups from that which is exercised within endogroups?

You can distinguish this if you wish, but all social violence is "validated" simply by identifying another social group--either endo- or exogroups--as different, as in the wrong in some way, and as enemy. That's basically all it takes, unfortunately, for animosity among all too many average humans to fulminate into violence.

3.-Are game theory and multilevel selection useful to explain these group dynamics?

3.-Are game theory and multilevel selection useful to explain these group dynamics?

Maybe. But let's face it, violence is underlain by emotions. Sure, logic is important to the human brain (and maybe even to the chimpanzee brain), but emotion ultimately rules human behavior. And evolution has programmed all of our emotions to maximize our survival and reproductive success by prompting us to act, sometimes violently, when we seem to be in a position to gain from it. How well does game theory compute or integrate emotion?

4.-In order to reinforce links within each group, does inter group violence need of other social instincts, such as loyalty, companionship, altruism...?

Social violence would probably not happen at all without loyalty, companionship, altruism--all of which based upon kin selection and/or reciprocal altruism.

5.- Speaking of violence against exogroups: to what extent or in what circumstances is war a result of the struggle for scarce resources, as noted by Marvin Harris?

The most important book on this facet of violence is Thomas F. Homer-Dixon's Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (1999). Were I to have only two books on my shelf about violence, they would consist of my own The Dark Side of Man, and Homer-Dixon's well-researched book. In contrast, Marvin Harris' work is based on social ideas emanating from the group selectionist social sciences, a concept proven again and again to be fallacious by evolutionary biology. I am, therefore not a fan of Harris' work or ideas. But, having said that, all violence is aimed at stealing. And when environmental scarcity--or even mere imagined resource scarcity--enters the picture, the fuse is automatically lit to detonate violence

The most important book on this facet of violence is Thomas F. Homer-Dixon's Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (1999). Were I to have only two books on my shelf about violence, they would consist of my own The Dark Side of Man, and Homer-Dixon's well-researched book. In contrast, Marvin Harris' work is based on social ideas emanating from the group selectionist social sciences, a concept proven again and again to be fallacious by evolutionary biology. I am, therefore not a fan of Harris' work or ideas. But, having said that, all violence is aimed at stealing. And when environmental scarcity--or even mere imagined resource scarcity--enters the picture, the fuse is automatically lit to detonate violence

6.-What role does threat play, generally speaking, in violence?

6.-What role does threat play, generally speaking, in violence?

Threat is the tool that offenders use to avoid the expense or risk of actually attempting to engage in violence to steal whatever they desire from their victim(s). Threats are not all genuine. Many threats can be bluffs. The threatening person(s) have no intention of risking themselves to inflict violence, but they believe a fair chance exists that their victims will believe that the threat is genuine and thus give up whatever the perpetrator is demanding. This is, of course, cowardly, but still violent. Threats also can be genuine: the perpetrator does fully intend to use violence to steal what he wants, but he is happier yet to take no real risk to do so. Potential victims must generally treat all threats as real and pre-empt the threatenor with decisive defensive action. In short, all threats must be considered as violence in and of themselves.

7.-To what extent is violence a defense, rather than an attack?

7.-To what extent is violence a defense, rather than an attack?

In nearly all martial arts, all violent techniques and skills are taught in a defensive context. So much so that the perfect martial artist would never need to employ his or her skills violently if he/she exercised perfect vigilance to avoid offensive action against them. If, however, vigilance fails to avoid conflict, many martial arts teach devastating and lethal responses to attack. The offender would normally be killed. So, if I understand your question correctly, it is either completely open-ended, or else meaningless. Defending oneself justifiably can be more violent, but again justified, than the offending violence by the perpetrator who initiated the confrontation.

The only defense against violence, by the way, is the willingness to perform even more violence in response in self defense.

8.-There is now in Spain a lot of talking about gender violence, or machismo violence, referring to violence exercised by a man over a woman (usually his partner or ex-partner), as if it were an assault of all men on all women. What do you think about this thorny issue?

8.-There is now in Spain a lot of talking about gender violence, or machismo violence, referring to violence exercised by a man over a woman (usually his partner or ex-partner), as if it were an assault of all men on all women. What do you think about this thorny issue?

Personally, I do not think the issue is so thorny. The assaults on women by men are a one-on-one phenomenon. and are heinous on a case by case basis. Saying that they are an assault by all men on all women are silly and wrong in this context. On the other hand, they are accurate as hell if the social laws designed by a society to combat this are ineffective in execution or gravity. In short, if a society provides only legal lip-service saying male aggression against women is bad but in reality fails to protect women by exerting strong lex talionis justice against convicted offenders (whether male or female), then that society is saying it condones a societal lifestyle in which it is okay that there exists an active state of assault of all men against all women (a bit like what has been portrayed to take place in Saudi Arabia)

9.-Can laws significantly decrease the number of cases of this kind of violence, or is it an attempt doomed to failure?

9.-Can laws significantly decrease the number of cases of this kind of violence, or is it an attempt doomed to failure?

Laws against anything, including machismo violence against women, are useful or effective only based on the level to which the society making those laws is willing to punish offenders. If, for instance, all men convicted of machismo violence against women were castrated then decapitated in the public square immediately after their trials, with no legal appeals, the level of violence against women would nearly vanish. Let's face it. most men are far more powerful and more damagingly violent than women are, and women know it. This is how mere threats of violence by men are effective in coercing a woman to capitulate to the demands of a male aggressor. Men are so aware of this that one of the normal first tactics that male rapists use against women is the threat that they will hurt her unless she capitulates to copulation, etc. Again, the verbal threat of violence is, in my opinion, equal in gravity and violence to the actual violence itself.

The bottom line here is that a social group that wishes to protect women from the abuse of men must be willing to punish convicted men so severely that they will never be able to hurt their victim again. This means long imprisonment, and upon release from prison (should this occur), mandatory effective locked-GPS-radio-dogcollaring upon release preventing the man from ever being within 20 km of their victi--for life. All too often the legal system releases a violent offender who then makes a bee-line to his previous victim to abuse or murder her. This sort of thing is a failure of society and the legal system, a failure which is inexcusable and unacceptable. If people are willing to face this challenge of making and enforcing laws fully, then it should be no big problem. If, instead, the laws are merely for political "show," and ineffective in enforcement, then the issue does become "thorny."

10.-Are religions a source of violence, as suggested by Dawkins?

10.-Are religions a source of violence, as suggested by Dawkins?

I was raised a Roman Catholic. Despite this, I have to agree that the very worst invention of the human species --an invention that has been re-invented independently by many societies across the Earth-- is the invention of organized religion. Sad to say, but it is true that organized religion has been misused endlessly as the springboard of "righteousness" validating the murder and pillaging of more innocent human beings in the world across history than all other rationales for violence in mankind's sordid history. This scourge is still so evident in our world of today's nonstop fatwas of lethal terrorism in the name of Allah, that it hardly needs mentioning. This murderous history of organized religion, unfortunately, is paradoxically in complete contradiction to the wisdom of all the world's greatest prophets, including Buddha, Christ, Mohammed, and so on, upon whose teachings these organized religions are ostensibly based.

Go figure.

11.-It was discovered long ago that chimps are not peaceful, and that they practice infanticide and other kinds of intraspecific killing. Bonobos are not particularly peaceful, but they tend to resolve conflicts sexually and females have a more prominent role in their societies. Frans de Waal in "Our Inner Ape" said man goes something in between these two species where aggressive tendencies are concerned. Are we more bonobos or more chimps?

11.-It was discovered long ago that chimps are not peaceful, and that they practice infanticide and other kinds of intraspecific killing. Bonobos are not particularly peaceful, but they tend to resolve conflicts sexually and females have a more prominent role in their societies. Frans de Waal in "Our Inner Ape" said man goes something in between these two species where aggressive tendencies are concerned. Are we more bonobos or more chimps?

We are more like chimps. Bonobos, too, are more like chimps than most writers are will to admit.

12.- How do you evolutionarily explain violence?

12.- How do you evolutionarily explain violence?

Violence of all sorts seen in the natural living world --including that perpetrated by humans against one another or against other species or against entire ecosystems-- is almost always simply one natural strategy "chosen" out of an array of evolutionary strategies available to (or instinctually programmed into) the perpetrator to steal something from the victim. This something can be the victim's body, sexual reproductive capacity, territory, resources, goods, money, spouse(s), et cetera. Violence can be the perpetrator's strategy of last resort when other strategies gave failed. Or, instead, violence can be simply the strategy of greatest ease for the perpetrator. Or, by default, violence can be the strategy requiring the least intelligent cogitation on the part of the perpetrator. Perpetrators generally use violence when they imagine they are facing a victim (or opponent) unable to retaliate with equal or superior violent capacity. In short, violent perpetrators seek prey less dangerous than themselves.

That which violent perpetrators generally steal--or seek to steal--are resources that directly or indirectly foster increased reproductive success. These can include the obvious examples such as a male rapist raping a woman who generally would not consent to mate with that specific man under any under other circumstances. Hence he decides rape (which hinges upon violence and/or the threat of violence to coerce his victim) is his only certain way of his copulating with her. Or the perpetrator can be seeking money in a robbery. In that women are more attracted to men (all else being equal) with greater obvious wealth, robbery can translate to greater opportunity for sex and reproduction. Perpetrators can be a coordinated social group--such as a nation's army--aggressing together to steal a neighboring nation's territory and the resources therein. The sophistries used to justify such violence can be religious or political, but such propaganda is a mere veneer for the deeper, ancient evolutionary instinct to simply reproduce more of one's genes by stealing and using the resources and/or women belonging to another, less- genetically similar group. On both an individual and social level, the use of violence is inextricably linked to increasing one's social status among nearly all social species, including humans (watch what happens in any unsupervised group of boys). Status simply means having preferential access to limited but important resources needed by one's conspecifics. Gaining preferential access usually translates to increased survival and reproductive success.

That which violent perpetrators generally steal--or seek to steal--are resources that directly or indirectly foster increased reproductive success. These can include the obvious examples such as a male rapist raping a woman who generally would not consent to mate with that specific man under any under other circumstances. Hence he decides rape (which hinges upon violence and/or the threat of violence to coerce his victim) is his only certain way of his copulating with her. Or the perpetrator can be seeking money in a robbery. In that women are more attracted to men (all else being equal) with greater obvious wealth, robbery can translate to greater opportunity for sex and reproduction. Perpetrators can be a coordinated social group--such as a nation's army--aggressing together to steal a neighboring nation's territory and the resources therein. The sophistries used to justify such violence can be religious or political, but such propaganda is a mere veneer for the deeper, ancient evolutionary instinct to simply reproduce more of one's genes by stealing and using the resources and/or women belonging to another, less- genetically similar group. On both an individual and social level, the use of violence is inextricably linked to increasing one's social status among nearly all social species, including humans (watch what happens in any unsupervised group of boys). Status simply means having preferential access to limited but important resources needed by one's conspecifics. Gaining preferential access usually translates to increased survival and reproductive success.

One huge difference in the manifestation of violence exists between the sexes among humans. Women generally only employ violence to protect themselves or their reproductive interests. Men, however, can and do employ violence to expand their reproductive interests. In that this expansion can extend beyond all horizons, the capacity for male violence--either perpetrated by individual men or by groups of men--can tend toward limitless violence. Nearly all of this is natural and instinctive, having been increasingly coded into our genes by natural selection and sexual selection through the greater reproductive success of violent individuals, but our awareness of this should not in any way be translated to mean that offensive violence is somehow good. Male violence is the scourge of humanity and the writer of its brutal history for the past 10,000 years. It is nothing to be proud of and nothing to emulate. But our ability as social and responsible individuals to reduce violence among ourselves and our peers cannot help but be enhanced by our understanding of its roots, manifestations, and the sorts of responses we pit against violence which prove most effective in reducing it. To conquer it, we must understand it.

1.-What is the difference between violence exercised by individuals and by groups? Can we speak of a micro and a macroviolence?

1.-What is the difference between violence exercised by individuals and by groups? Can we speak of a micro and a macroviolence?As far as I see it, the differences between violence exercised between individuals versus that between groups mainly revolve around the perceived or imagined idea that the risk(s) to the perpetrators seems to be less for individuals in the group than the risk to be incurred by one man were he to go out in single combat against a single enemy opponent. In a group, each man may each imagine that someone else among them will be the one who suffers, not him. The other major difference is various sorts of propaganda or polemics or political discussion emerges as emotional grease to validate in advance an offensive by a social group, whereas nearly nothing of this sort occurs before one individual commits offensive violence.

I think distinctions made in the spectrum of violence as "macro" and "micro-" violence are silly. How many times does one need to be beat up or murdered to begin thinking of any violence as "micro?" In short, violence is employed mainly to steal what the victim has, whether that victim is a single young woman or a neighboring nation. Once a certain level of violence has attained its goal--the surrendering of what the aggressor(s) want to steal--the need for violence has passed. Sometimes mere coercion (as is the ultimate goal of terrorism) by threat is all that is needed. But when no violence at all occurs except words of threat, can we call it "micro?" I think not. All violence is "macro."

2.-Regarding the violence exercised by groups, could we distinguish that exerted towards exogroups from that which is exercised within endogroups?

2.-Regarding the violence exercised by groups, could we distinguish that exerted towards exogroups from that which is exercised within endogroups?You can distinguish this if you wish, but all social violence is "validated" simply by identifying another social group--either endo- or exogroups--as different, as in the wrong in some way, and as enemy. That's basically all it takes, unfortunately, for animosity among all too many average humans to fulminate into violence.

3.-Are game theory and multilevel selection useful to explain these group dynamics?

3.-Are game theory and multilevel selection useful to explain these group dynamics?Maybe. But let's face it, violence is underlain by emotions. Sure, logic is important to the human brain (and maybe even to the chimpanzee brain), but emotion ultimately rules human behavior. And evolution has programmed all of our emotions to maximize our survival and reproductive success by prompting us to act, sometimes violently, when we seem to be in a position to gain from it. How well does game theory compute or integrate emotion?

4.-In order to reinforce links within each group, does inter group violence need of other social instincts, such as loyalty, companionship, altruism...?

Social violence would probably not happen at all without loyalty, companionship, altruism--all of which based upon kin selection and/or reciprocal altruism.

5.- Speaking of violence against exogroups: to what extent or in what circumstances is war a result of the struggle for scarce resources, as noted by Marvin Harris?

The most important book on this facet of violence is Thomas F. Homer-Dixon's Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (1999). Were I to have only two books on my shelf about violence, they would consist of my own The Dark Side of Man, and Homer-Dixon's well-researched book. In contrast, Marvin Harris' work is based on social ideas emanating from the group selectionist social sciences, a concept proven again and again to be fallacious by evolutionary biology. I am, therefore not a fan of Harris' work or ideas. But, having said that, all violence is aimed at stealing. And when environmental scarcity--or even mere imagined resource scarcity--enters the picture, the fuse is automatically lit to detonate violence

The most important book on this facet of violence is Thomas F. Homer-Dixon's Environment, Scarcity, and Violence (1999). Were I to have only two books on my shelf about violence, they would consist of my own The Dark Side of Man, and Homer-Dixon's well-researched book. In contrast, Marvin Harris' work is based on social ideas emanating from the group selectionist social sciences, a concept proven again and again to be fallacious by evolutionary biology. I am, therefore not a fan of Harris' work or ideas. But, having said that, all violence is aimed at stealing. And when environmental scarcity--or even mere imagined resource scarcity--enters the picture, the fuse is automatically lit to detonate violence 6.-What role does threat play, generally speaking, in violence?

6.-What role does threat play, generally speaking, in violence?Threat is the tool that offenders use to avoid the expense or risk of actually attempting to engage in violence to steal whatever they desire from their victim(s). Threats are not all genuine. Many threats can be bluffs. The threatening person(s) have no intention of risking themselves to inflict violence, but they believe a fair chance exists that their victims will believe that the threat is genuine and thus give up whatever the perpetrator is demanding. This is, of course, cowardly, but still violent. Threats also can be genuine: the perpetrator does fully intend to use violence to steal what he wants, but he is happier yet to take no real risk to do so. Potential victims must generally treat all threats as real and pre-empt the threatenor with decisive defensive action. In short, all threats must be considered as violence in and of themselves.

7.-To what extent is violence a defense, rather than an attack?

7.-To what extent is violence a defense, rather than an attack?In nearly all martial arts, all violent techniques and skills are taught in a defensive context. So much so that the perfect martial artist would never need to employ his or her skills violently if he/she exercised perfect vigilance to avoid offensive action against them. If, however, vigilance fails to avoid conflict, many martial arts teach devastating and lethal responses to attack. The offender would normally be killed. So, if I understand your question correctly, it is either completely open-ended, or else meaningless. Defending oneself justifiably can be more violent, but again justified, than the offending violence by the perpetrator who initiated the confrontation.

The only defense against violence, by the way, is the willingness to perform even more violence in response in self defense.

8.-There is now in Spain a lot of talking about gender violence, or machismo violence, referring to violence exercised by a man over a woman (usually his partner or ex-partner), as if it were an assault of all men on all women. What do you think about this thorny issue?

8.-There is now in Spain a lot of talking about gender violence, or machismo violence, referring to violence exercised by a man over a woman (usually his partner or ex-partner), as if it were an assault of all men on all women. What do you think about this thorny issue?Personally, I do not think the issue is so thorny. The assaults on women by men are a one-on-one phenomenon. and are heinous on a case by case basis. Saying that they are an assault by all men on all women are silly and wrong in this context. On the other hand, they are accurate as hell if the social laws designed by a society to combat this are ineffective in execution or gravity. In short, if a society provides only legal lip-service saying male aggression against women is bad but in reality fails to protect women by exerting strong lex talionis justice against convicted offenders (whether male or female), then that society is saying it condones a societal lifestyle in which it is okay that there exists an active state of assault of all men against all women (a bit like what has been portrayed to take place in Saudi Arabia)

9.-Can laws significantly decrease the number of cases of this kind of violence, or is it an attempt doomed to failure?

9.-Can laws significantly decrease the number of cases of this kind of violence, or is it an attempt doomed to failure?Laws against anything, including machismo violence against women, are useful or effective only based on the level to which the society making those laws is willing to punish offenders. If, for instance, all men convicted of machismo violence against women were castrated then decapitated in the public square immediately after their trials, with no legal appeals, the level of violence against women would nearly vanish. Let's face it. most men are far more powerful and more damagingly violent than women are, and women know it. This is how mere threats of violence by men are effective in coercing a woman to capitulate to the demands of a male aggressor. Men are so aware of this that one of the normal first tactics that male rapists use against women is the threat that they will hurt her unless she capitulates to copulation, etc. Again, the verbal threat of violence is, in my opinion, equal in gravity and violence to the actual violence itself.

The bottom line here is that a social group that wishes to protect women from the abuse of men must be willing to punish convicted men so severely that they will never be able to hurt their victim again. This means long imprisonment, and upon release from prison (should this occur), mandatory effective locked-GPS-radio-dogcollaring upon release preventing the man from ever being within 20 km of their victi--for life. All too often the legal system releases a violent offender who then makes a bee-line to his previous victim to abuse or murder her. This sort of thing is a failure of society and the legal system, a failure which is inexcusable and unacceptable. If people are willing to face this challenge of making and enforcing laws fully, then it should be no big problem. If, instead, the laws are merely for political "show," and ineffective in enforcement, then the issue does become "thorny."

10.-Are religions a source of violence, as suggested by Dawkins?

10.-Are religions a source of violence, as suggested by Dawkins?I was raised a Roman Catholic. Despite this, I have to agree that the very worst invention of the human species --an invention that has been re-invented independently by many societies across the Earth-- is the invention of organized religion. Sad to say, but it is true that organized religion has been misused endlessly as the springboard of "righteousness" validating the murder and pillaging of more innocent human beings in the world across history than all other rationales for violence in mankind's sordid history. This scourge is still so evident in our world of today's nonstop fatwas of lethal terrorism in the name of Allah, that it hardly needs mentioning. This murderous history of organized religion, unfortunately, is paradoxically in complete contradiction to the wisdom of all the world's greatest prophets, including Buddha, Christ, Mohammed, and so on, upon whose teachings these organized religions are ostensibly based.

Go figure.

11.-It was discovered long ago that chimps are not peaceful, and that they practice infanticide and other kinds of intraspecific killing. Bonobos are not particularly peaceful, but they tend to resolve conflicts sexually and females have a more prominent role in their societies. Frans de Waal in "Our Inner Ape" said man goes something in between these two species where aggressive tendencies are concerned. Are we more bonobos or more chimps?

11.-It was discovered long ago that chimps are not peaceful, and that they practice infanticide and other kinds of intraspecific killing. Bonobos are not particularly peaceful, but they tend to resolve conflicts sexually and females have a more prominent role in their societies. Frans de Waal in "Our Inner Ape" said man goes something in between these two species where aggressive tendencies are concerned. Are we more bonobos or more chimps?We are more like chimps. Bonobos, too, are more like chimps than most writers are will to admit.

12.- How do you evolutionarily explain violence?

12.- How do you evolutionarily explain violence?Violence of all sorts seen in the natural living world --including that perpetrated by humans against one another or against other species or against entire ecosystems-- is almost always simply one natural strategy "chosen" out of an array of evolutionary strategies available to (or instinctually programmed into) the perpetrator to steal something from the victim. This something can be the victim's body, sexual reproductive capacity, territory, resources, goods, money, spouse(s), et cetera. Violence can be the perpetrator's strategy of last resort when other strategies gave failed. Or, instead, violence can be simply the strategy of greatest ease for the perpetrator. Or, by default, violence can be the strategy requiring the least intelligent cogitation on the part of the perpetrator. Perpetrators generally use violence when they imagine they are facing a victim (or opponent) unable to retaliate with equal or superior violent capacity. In short, violent perpetrators seek prey less dangerous than themselves.

That which violent perpetrators generally steal--or seek to steal--are resources that directly or indirectly foster increased reproductive success. These can include the obvious examples such as a male rapist raping a woman who generally would not consent to mate with that specific man under any under other circumstances. Hence he decides rape (which hinges upon violence and/or the threat of violence to coerce his victim) is his only certain way of his copulating with her. Or the perpetrator can be seeking money in a robbery. In that women are more attracted to men (all else being equal) with greater obvious wealth, robbery can translate to greater opportunity for sex and reproduction. Perpetrators can be a coordinated social group--such as a nation's army--aggressing together to steal a neighboring nation's territory and the resources therein. The sophistries used to justify such violence can be religious or political, but such propaganda is a mere veneer for the deeper, ancient evolutionary instinct to simply reproduce more of one's genes by stealing and using the resources and/or women belonging to another, less- genetically similar group. On both an individual and social level, the use of violence is inextricably linked to increasing one's social status among nearly all social species, including humans (watch what happens in any unsupervised group of boys). Status simply means having preferential access to limited but important resources needed by one's conspecifics. Gaining preferential access usually translates to increased survival and reproductive success.

That which violent perpetrators generally steal--or seek to steal--are resources that directly or indirectly foster increased reproductive success. These can include the obvious examples such as a male rapist raping a woman who generally would not consent to mate with that specific man under any under other circumstances. Hence he decides rape (which hinges upon violence and/or the threat of violence to coerce his victim) is his only certain way of his copulating with her. Or the perpetrator can be seeking money in a robbery. In that women are more attracted to men (all else being equal) with greater obvious wealth, robbery can translate to greater opportunity for sex and reproduction. Perpetrators can be a coordinated social group--such as a nation's army--aggressing together to steal a neighboring nation's territory and the resources therein. The sophistries used to justify such violence can be religious or political, but such propaganda is a mere veneer for the deeper, ancient evolutionary instinct to simply reproduce more of one's genes by stealing and using the resources and/or women belonging to another, less- genetically similar group. On both an individual and social level, the use of violence is inextricably linked to increasing one's social status among nearly all social species, including humans (watch what happens in any unsupervised group of boys). Status simply means having preferential access to limited but important resources needed by one's conspecifics. Gaining preferential access usually translates to increased survival and reproductive success.One huge difference in the manifestation of violence exists between the sexes among humans. Women generally only employ violence to protect themselves or their reproductive interests. Men, however, can and do employ violence to expand their reproductive interests. In that this expansion can extend beyond all horizons, the capacity for male violence--either perpetrated by individual men or by groups of men--can tend toward limitless violence. Nearly all of this is natural and instinctive, having been increasingly coded into our genes by natural selection and sexual selection through the greater reproductive success of violent individuals, but our awareness of this should not in any way be translated to mean that offensive violence is somehow good. Male violence is the scourge of humanity and the writer of its brutal history for the past 10,000 years. It is nothing to be proud of and nothing to emulate. But our ability as social and responsible individuals to reduce violence among ourselves and our peers cannot help but be enhanced by our understanding of its roots, manifestations, and the sorts of responses we pit against violence which prove most effective in reducing it. To conquer it, we must understand it.

En castellano:

1.-¿Cuál es la diferencia entre la violencia ejercida por individuos y por grupos? ¿Puede hablarse de micro y macroviolencia?

1.-¿Cuál es la diferencia entre la violencia ejercida por individuos y por grupos? ¿Puede hablarse de micro y macroviolencia?Hasta donde yo lo veo, las diferencias entre la violencia ejercida entre individuos y la ejercida entre grupos pivotan principalmente sobre la idea percibida o imaginada de que el riesgo (o riesgos) para los perpetradores parece ser menor para los individuos del grupo que el riesgo en el que incurriría un solo hombre si hubiera de enfrentarse en combate singular a un solo oponente enemigo. En un grupo, cada hombre puede imaginar que algún otro de entre ellos será el que sufra, y no él. La otra diferencia importante es que varias clases de propaganda, de polémica o de discusión política emergen como lubricante emocional para validar por anticipado una ofensiva por parte de un grupo social, mientras que casi nada de esta clase ocurre antes de que un individuo cometa violencia ofensiva.

Creo que las distinciones entre "macro" y "micro" en el espectro de la violencia son una tontería. ¿Cuántas veces hace falta que te den una paliza o te asesinen para empezar a pensar de cualquier violencia que es "micro"? Brevemente, la violencia se usa principalmente para robar algo que la víctima tiene, ya sea esa víctima una mujer soltera o una nación vecina. Una vez que un cierto nivel de violencia ha alcanzado su objetivo —la entrega de lo que el agresor (o agresores) quiere robar— la necesidad de violencia ha cesado. A veces la mera coerción (como es el objetivo final del terrorismo) por la amenaza es todo lo que hace falta. Pero cuando no hay violencia en absoluto excepto las palabras de amenaza, ¿podemos llamarla "micro"? Creo que no. Toda violencia es "macro".

2.-Respecto a la violencia ejercida por grupos, ¿podríamos distinguir entre la ejercida hacia exogrupos de la ejercida en el endogrupo?

2.-Respecto a la violencia ejercida por grupos, ¿podríamos distinguir entre la ejercida hacia exogrupos de la ejercida en el endogrupo?Puede usted distinguirlas si quiere, pero toda violencia social es "validada" simplemente identificando otro grupo social —ya endo, ya exogrupos— como diferente, como reprobable en algo, y como enemigo. Esto es básicamente todo lo que hace falta, desafortunadamente, entre enteramente demasiados humanos corrientes, para que la animosidad estalle en violencia.

3.-¿Son útiles la teoría de juegos y la selección multinivel para explicar estas dinámicas de grupo?

Es posible. Pero, afrontémoslo, a la violencia subyacen emociones. Cierto, la lógica es importante para el cerebro humano (y tal vez incluso para el cerebro chimpancé), pero la emoción es lo que gobierna en definitiva la conducta humana. Y la evolución ha programado todas nuestras emociones para maximizar nuestra supervivencia y éxito reproductivo impulsándonos a actuar, a veces violentamente, cuando parezca que estamos en una situación en la que podamos obtener provecho de ello. ¿Qué tal computa o integra las emociones la teoría de juegos?

4.-Para reforzar los lazos dentro de cada grupo, ¿necesita la violencia intergrupal de otros instintos sociales, como la lealtad, el compañerismo, el altruismo...?

4.-Para reforzar los lazos dentro de cada grupo, ¿necesita la violencia intergrupal de otros instintos sociales, como la lealtad, el compañerismo, el altruismo...?La violencia social probablemente no ocurriría en absoluto sin lealtad, compañerismo, altruismo... todos los cuales se basan en la selección de parentesco y/o el altruismo recíproco.

5.-Hablando de la violencia contra exogrupos: ¿hasta qué punto o en qué circunstancias es la guerra un resultado de la lucha por recursos escasos, como notó Marvin Harris?

5.-Hablando de la violencia contra exogrupos: ¿hasta qué punto o en qué circunstancias es la guerra un resultado de la lucha por recursos escasos, como notó Marvin Harris?El libro más importante sobre este aspecto de la violencia es el de Thomas F. Homer-Dixon Environment, Scarcity and Violence (1999). Si hubiera yo de tener sólo dos textos sobre la violencia en mi biblioteca, serían mi propio The Dark Side of Man y el bien investigado libro de Homer-Dixon. En contraste, la obra de Marvin Harris está basada en en ideas sociales que emanan de las ciencias sociales partidarias de la selección de grupo, un concepto que la biología evolucionista ha demostrado repetidamente que es falaz. No soy, por tanto, un fan de la obra o las ideas de Marvin Harris. Pero, dicho esto, toda violencia apunta al robo. Y cuando la escasez ambiental —o aun una meramente imaginada escasez de algún recurso— entra en el cuadro, automáticamente se enciende el detonador para hacer estallar la violencia.

6.-¿Qué papel desempeña la amenaza, en términos generales, en la violencia?

6.-¿Qué papel desempeña la amenaza, en términos generales, en la violencia?La amenaza es el instrumento que usan los ofensores para evitar el gasto o riesgo de intentar efectivamente el uso de la violencia para robar lo que sea que deseen de su víctima (o víctimas). Las amenazas no siempre son genuinas. Muchas amenazas pueden ser baladronadas. La persona (o personas) que amenaza no tiene ninguna intención de arriesgarse a infligir violencia, pero cree que hay una buena probabilidad de que sus víctimas creerán que la amenaza es genuina y por tanto entregarán lo que el perpetrador exige. Esto es, por supuesto, cobarde, pero sigue siendo violento. Las amenazas también pueden ser genuinas: el perpetrador tiene toda la intención de usar violencia para robar lo que quiere, pero queda aún más contento si no corre ningún riesgo al hacerlo. Las víctimas en potencia deben en general tratar todas las amenazas como reales y responder a quien amenaza con una acción defensiva decisiva. En suma, todas las amenazas deben considerarse violencia en sí mismas.

7.-¿Con que extensión es la violencia una defensa, más que un ataque?

7.-¿Con que extensión es la violencia una defensa, más que un ataque?En casi todas las artes marciales, todas las técnicas y aptitudes violentas se enseñan en un contexto defensivo. Tan es así que el (o la) perfecto artista marcial nunca necesitaría emplear sus habilidades violentamente si ejerciese perfecta vigilancia para evitar acciones ofensivas en su contra. Si, sin embargo, la vigilancia no consigue evitar el conflicto, muchas artes marciales enseñan devastadoras y letales respuestas al ataque. El atacante, normalmente, resultaría muerto. Así pues, si entiendo correctamente su pregunta, o no tiene ninguna respuesta sencilla o carece de sentido. Defenderse justificadamente puede ser más violento, pero, repito, justificado, que la violencia del perpetrador que inició la confrontación.

La única defensa contra la violencia, por cierto, es la disposición a ejercer aún más violencia en respuesta en autodefensa.

8.-Se habla mucho hoy en España sobre la violencia de género, o violencia machista, refiriéndose a la violencia ejercida por un hombre sobre una mujer (generalmente su pareja o expareja), como si esto fuera una asalto de todos los hombres sobre todas las mujeres. ¿Qué opinión le merece este espinoso asunto?

8.-Se habla mucho hoy en España sobre la violencia de género, o violencia machista, refiriéndose a la violencia ejercida por un hombre sobre una mujer (generalmente su pareja o expareja), como si esto fuera una asalto de todos los hombres sobre todas las mujeres. ¿Qué opinión le merece este espinoso asunto?Personalmente, no creo que la cuestión sea tan espinosa. Los ataques de varones a mujeres son un fenómeno individual y son odiosos caso por caso. Decir que son un asalto de todos los varones a todas las mujeres es una tontería y erróneo en este contexto. Por otra parte, es del todo preciso si las leyes sociales diseñadas por una sociedad para combatirlos son inefectivas en ejecución o severidad. En suma, si una sociedad proporciona sólo una sanción legal de boquilla que dice que la agresión masculina contra las mujeres es mala pero en realidad no protege efectivamente a las mujeres ejerciendo una justicia fuerte, una ley del talión, contra los atacantes convictos (ya sean varones o mujeres), entonces lo que esa sociedad está diciendo en realidad es que acepta un estilo de vida social en el que no está mal que haya un estado activo de asalto de todos los varones contra todas las mujeres (un poco como lo que se informa que ocurre en Arabia Saudí).

9.-¿Pueden las leyes hacer decrecer significativamente el número de casos de esta clase de violencia, o se trataría de unas tentativas condenadas al fracaso?

9.-¿Pueden las leyes hacer decrecer significativamente el número de casos de esta clase de violencia, o se trataría de unas tentativas condenadas al fracaso?Las leyes contra cualquier cosa, incluida la violencia machista contra las mujeres, son útiles o efectivas sólo en la medida en que la sociedad que hace esas leyes está dispuesta a castigar a los ofensores. Si, por ejemplo, todos los varones convictos de violencia machista contra mujeres fueran castrados y luego decapitados en la plaza pública inmediatamente después del juicio, sin apelación, la violencia contra las mujeres casi desaparecería. Afrontémoslo. La mayoría de los varones son mucho más fuertes y más violentos que las mujeres, y las mujeres lo saben. Así es cómo meras amenazas de violencia por varones son efectivas para obligar a una mujer a capitular ante las demandas de un agresor masculino. Los varones son tan conscientes de esto que normalmente una de las primeras tácticas que los violadores usan contra las mujeres es la amenaza de dañarlas a menos que capitulen a la copulación, etcétera. Repito que la amenaza verbal de violencia es, en mi opinión, igual en gravedad y violencia a la violencia de hecho en sí.

Lo esencial aquí es que un grupo social que desee proteger a las mujeres de los abusos de los varones debe estar dispuesto a castigar a los varones convictos tan severamente que jamás sean capaces de volver a dañar a su víctima. Esto significa largos encarcelamientos y, al ser liberados de la prisión (si esto ocurriese), colocación obligatoria de un collar bloqueado con radiolocalización y GPS que evite eficazmente que el hombre se acerque a 20 kilómetros de su víctima, de por vida. Demasiado a menudo el sistema legal pone en libertad a un ofensor violento que inmediatamente se dirige en línea recta a su anterior víctima para agredirla o asesinarla. Esta clase de cosas es un fracaso de la sociedad y del sistema legal, un fracaso que es inexcusable e inaceptable. Si la gente está dispuesta a afrontar este desafío de hacer leyes y hacerlas cumplir por completo, entonces no debería ser un gran problema. Si, en cambio, las leyes están solamente como espectáculo político, y su cumplimiento es inefectivo, entonces la cuestión sí se vuelve "espinosa".

10.-¿Es la religión una fuente de violencia, tal y como sugiere Dawkins?

10.-¿Es la religión una fuente de violencia, tal y como sugiere Dawkins?Yo fui criado como católico romano. A pesar de esto, debo convenir en que la peor invención de la especie humana —reinventada independientemente por muchas sociedades por toda la Tierra— es la de la religión organizada. Es triste decirlo, pero es cierto que la religión organizada ha sido incesantemente mal usada como trampolín del sentimiento de "justicia" que ha validado el asesinato y pillaje de más seres humanos en el mundo a lo largo de toda la historia que todas las demás justificaciones de la violencia en la sórdida historia de la humanidad. Este azote es aún tan evidente en nuestro mundo de hoy con las incesantes fatwas de letal terrorismo en nombre de Alá que apenas es preciso mencionarlo. Esta historia de asesinato de la religión organizada, infortunadamente, está paradójicamente en completa contradicción con la sabiduría de todos los mayores profetas del mundo, incluídos Buda, Cristo, Mahoma, etcétera, en cuyas enseñanzas se basan ostensiblemente estas religiones organizadas.

Figúrese.

11.-Hace tiempo que se descubrió que los chimpancés no son pacíficos, y que practican el infanticidio y otras clases de asesinato. Los bonobos no son particularmente pacíficos, pero tienden a resolver conflictos sexualmente y las hembras tienen un papel más prominente en sus sociedades. Frans de Waal, en su libro “El Mono que Llevamos Dentro” decía que el hombre es alfo intermedio entre estas dos especies en lo que se refiere a las tendencias agresivas. ¿Somos más bonobos o chimpancés?

11.-Hace tiempo que se descubrió que los chimpancés no son pacíficos, y que practican el infanticidio y otras clases de asesinato. Los bonobos no son particularmente pacíficos, pero tienden a resolver conflictos sexualmente y las hembras tienen un papel más prominente en sus sociedades. Frans de Waal, en su libro “El Mono que Llevamos Dentro” decía que el hombre es alfo intermedio entre estas dos especies en lo que se refiere a las tendencias agresivas. ¿Somos más bonobos o chimpancés?Somos más como los chimpancés. Los bonobos también son más como los chimpancés que lo que la mayoría de los autores está dispuesta a admitir.

12.-¿Cómo explicaría la violencia evolutivamente?

La violencia de todas clases que se ve en el mundo viviente —incluida la perpetrada por seres humanos entre sí o contra otras especies o contra ecosistemas enteros— es casi siempre, simplemente, una estrategia natural "elegida" de entre un repertorio de estrategias evolutivas disponibles para (o instintualmente programadas en) el perpetrador para robar algo de la víctima. Este algo puede ser el cuerpo de la víctima, su capacidad reproductiva sexual, recursos territoriales, bienes, dinero, cónyuge(s), etcétera. La violencia puede ser la estrategia de último recurso del perpetrador cuando otras estrategias han fallado. O, en lugar de eso, la violencia puede ser simplemente la estrategia más cómoda para el perpetrador. O, por fin, la violencia puede ser la estrategia que requiera la mínima reflexión inteligente por parte del perpetrador. Los perpetradores generalmente usan la violencia cuando se enfrentan a una víctima (u oponente) incapaz de desquitarse con igual o superior violencia. En suma, los perpetradores violentos buscan presas menos peligrosas que ellos mismos.

La violencia de todas clases que se ve en el mundo viviente —incluida la perpetrada por seres humanos entre sí o contra otras especies o contra ecosistemas enteros— es casi siempre, simplemente, una estrategia natural "elegida" de entre un repertorio de estrategias evolutivas disponibles para (o instintualmente programadas en) el perpetrador para robar algo de la víctima. Este algo puede ser el cuerpo de la víctima, su capacidad reproductiva sexual, recursos territoriales, bienes, dinero, cónyuge(s), etcétera. La violencia puede ser la estrategia de último recurso del perpetrador cuando otras estrategias han fallado. O, en lugar de eso, la violencia puede ser simplemente la estrategia más cómoda para el perpetrador. O, por fin, la violencia puede ser la estrategia que requiera la mínima reflexión inteligente por parte del perpetrador. Los perpetradores generalmente usan la violencia cuando se enfrentan a una víctima (u oponente) incapaz de desquitarse con igual o superior violencia. En suma, los perpetradores violentos buscan presas menos peligrosas que ellos mismos. Lo que los perpetradores violentos generalmente roban —o buscan robar— son recursos que directa o indirectamente favorecen un aumento de su éxito reproductivo. Esto puede incluir los ejemplos obvios como el varón que viola a una mujer que generalmente no consentiría en emparejarse con él en ninguna otra circunstancia. Por tanto decide que la violación (que consiste en la violencia y/o la amenaza de violencia para obligar a su víctima) es la única manera segura de copular con ella. O el perpetrador puede buscar dinero en un atraco. Ya que a las mujeres las atraen más los varones (siendo lo demás igual) con mayor riqueza evidente, el atraco puede traducirse en más oportunidades para el sexo y la reproducción. Los perpetradores pueden ser un grupo social coordinado —como el ejército de una nación— que atacan juntos para robar territorio de una nación vecina y los recursos que haya en él. Las sofisterías usadas para justificar tal violencia pueden ser religiosas o políticas, pero esa propaganda es un mero revestimiento sobre el antiguo instinto evolutivo de, simplemente, reproducir más de los propios genes robando y usando los recursos y/o mujeres que pertenecen a otro grupo genéticamente menos similar. Tanto en un nivel individual como social, el uso de la violencia está inextricablemente unido al aumento del propio nivel social en casi todas las especies sociales, incluídos los humanos (fíjese en lo que ocurre en cualquier grupo de muchachos sin supervisión). Un status más alto simplemente significa que se tiene acceso preferencial a recursos limitados pero importantes, que los congéneres de uno necesitan. Obtener acceso preferencial suele traducirse en un aumento en la supervivencia y el éxito reproductivo.

Lo que los perpetradores violentos generalmente roban —o buscan robar— son recursos que directa o indirectamente favorecen un aumento de su éxito reproductivo. Esto puede incluir los ejemplos obvios como el varón que viola a una mujer que generalmente no consentiría en emparejarse con él en ninguna otra circunstancia. Por tanto decide que la violación (que consiste en la violencia y/o la amenaza de violencia para obligar a su víctima) es la única manera segura de copular con ella. O el perpetrador puede buscar dinero en un atraco. Ya que a las mujeres las atraen más los varones (siendo lo demás igual) con mayor riqueza evidente, el atraco puede traducirse en más oportunidades para el sexo y la reproducción. Los perpetradores pueden ser un grupo social coordinado —como el ejército de una nación— que atacan juntos para robar territorio de una nación vecina y los recursos que haya en él. Las sofisterías usadas para justificar tal violencia pueden ser religiosas o políticas, pero esa propaganda es un mero revestimiento sobre el antiguo instinto evolutivo de, simplemente, reproducir más de los propios genes robando y usando los recursos y/o mujeres que pertenecen a otro grupo genéticamente menos similar. Tanto en un nivel individual como social, el uso de la violencia está inextricablemente unido al aumento del propio nivel social en casi todas las especies sociales, incluídos los humanos (fíjese en lo que ocurre en cualquier grupo de muchachos sin supervisión). Un status más alto simplemente significa que se tiene acceso preferencial a recursos limitados pero importantes, que los congéneres de uno necesitan. Obtener acceso preferencial suele traducirse en un aumento en la supervivencia y el éxito reproductivo. Existe en los seres humanos una enorme diferencia en la manifestación de la violencia entre los sexos. Las mujeres en general usan la violencia sólo para protegerse a sí mismas o sus intereses reproductivos. Los varones, sin embargo, pueden emplear y emplean la violencia para expandir sus intereses reproductivos. Ya que esta expansión puede extenderse más allá de cualquier horizonte, la capacidad masculina para la violencia —perpetrada ya por varones individuales o por grupos de varones— puede tender a una violencia sin límites. Casi todo esto es natural e instintivo, codificado acumulativamente en nuestros genes por la selección natural y la selección sexual mediante el mayor éxito reproductivo de los individuos violentos, pero el ser conscientes de esto no debería de ninguna manera traducirse para significar que la violencia ofensiva sea de alguna manera buena. La violencia masculina es el azote de la Humanidad y el autor de su brutal historia durante los pasados 10.000 años. No es nada de lo que enorgullecerse ni que emular. Pero nuestra capacidad como individuos sociales y responsables para reducir la violencia entre nosotros y nuestros pares no puede sino verse ayudada por nuestra comprensión de sus raíces, sus manifestaciones y la clase de respuestas que oponemos a la violencia que se muestran más efectivas en reducirla. Para vencerla, debemos entenderla.

Existe en los seres humanos una enorme diferencia en la manifestación de la violencia entre los sexos. Las mujeres en general usan la violencia sólo para protegerse a sí mismas o sus intereses reproductivos. Los varones, sin embargo, pueden emplear y emplean la violencia para expandir sus intereses reproductivos. Ya que esta expansión puede extenderse más allá de cualquier horizonte, la capacidad masculina para la violencia —perpetrada ya por varones individuales o por grupos de varones— puede tender a una violencia sin límites. Casi todo esto es natural e instintivo, codificado acumulativamente en nuestros genes por la selección natural y la selección sexual mediante el mayor éxito reproductivo de los individuos violentos, pero el ser conscientes de esto no debería de ninguna manera traducirse para significar que la violencia ofensiva sea de alguna manera buena. La violencia masculina es el azote de la Humanidad y el autor de su brutal historia durante los pasados 10.000 años. No es nada de lo que enorgullecerse ni que emular. Pero nuestra capacidad como individuos sociales y responsables para reducir la violencia entre nosotros y nuestros pares no puede sino verse ayudada por nuestra comprensión de sus raíces, sus manifestaciones y la clase de respuestas que oponemos a la violencia que se muestran más efectivas en reducirla. Para vencerla, debemos entenderla.

Este comentario ha sido eliminado por el autor.

ResponderEliminar¡Pues no dejes de leer su libro!

ResponderEliminarExcelente nota.

ResponderEliminar